Counting castes in India has always been about more than numbers - it is about who gets a share of government benefits and who doesn't. The country's next national census, scheduled for 2027, will - for the first time in nearly a century - count every caste, a social hierarchy that has long outlived kingdoms, empires, and ideologies. The move ends decades of political hesitation and follows pressure from opposition parties and at least three states that have already gone ahead with their own surveys. Advocates for a full caste count say it promises a sharper picture of welfare distribution and could recalibrate quotas in jobs and education based on hard evidence.

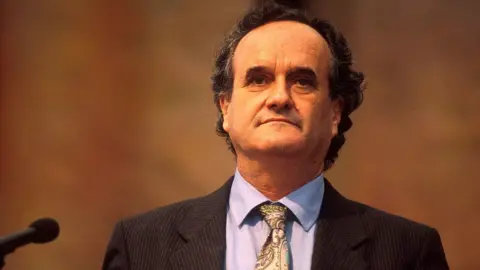

Yet, in a provocative new book, 'The Caste Con Census,' scholar-activist Anand Teltumbde warns that the exercise could further entrench the caste system rather than dismantle it, arguing that caste is 'too pernicious to be managed for any progressive purpose.' His perspective challenges the belief that better data will yield fairer policies, suggesting instead that counting may inadvertently reinforce inequality.

Political analysts and sociologists express divided opinions on the move. Some view it as a vital step towards social equity, while others foresee potential exploitation of caste data for electoral gain. As the debate continues, it's clear that the decision to count castes is more than statistical; it reflects larger issues of identity, privilege, and social justice in modern India.

Yet, in a provocative new book, 'The Caste Con Census,' scholar-activist Anand Teltumbde warns that the exercise could further entrench the caste system rather than dismantle it, arguing that caste is 'too pernicious to be managed for any progressive purpose.' His perspective challenges the belief that better data will yield fairer policies, suggesting instead that counting may inadvertently reinforce inequality.

Political analysts and sociologists express divided opinions on the move. Some view it as a vital step towards social equity, while others foresee potential exploitation of caste data for electoral gain. As the debate continues, it's clear that the decision to count castes is more than statistical; it reflects larger issues of identity, privilege, and social justice in modern India.