There is a war-opposing network in the world, with two focal points: one of power led by the US president and one of spirit found here with the Holy Father, Viktor Orban said last week after meeting Pope Leo at the Vatican.

We draw strength, motivation, and blessing from both, said the Hungarian prime minister.

If his ally in the White House, US President Donald Trump, was on his mind, then his thoughts could well have turned to a tricky meeting that awaits him on Friday in Washington.

The man Trump has called a great leader, and who has long provoked admiration in Maga circles, suddenly finds himself in an unusual position - at odds with the US president on an issue of critical importance.

At the centre of those talks will be new US pressure on Hungary and Slovakia to wean themselves urgently off Russian oil - Trump's latest gambit in his efforts to pressurise Russia into ending its war on Ukraine.

Asked recently whether Trump had gone too far in imposing sanctions on Russia's two biggest oil companies, Orban said from a Hungarian point of view, yes.

Orban has been using his country's heavy dependence on Russian oil and gas to advance his own agenda in several ways. He has used it as a weapon to attack Brussels, as a means to maintain his good relations with Moscow, and as a platform upon which he hopes to win re-election next April in Hungary. He has promised cheap Russian energy to voters.

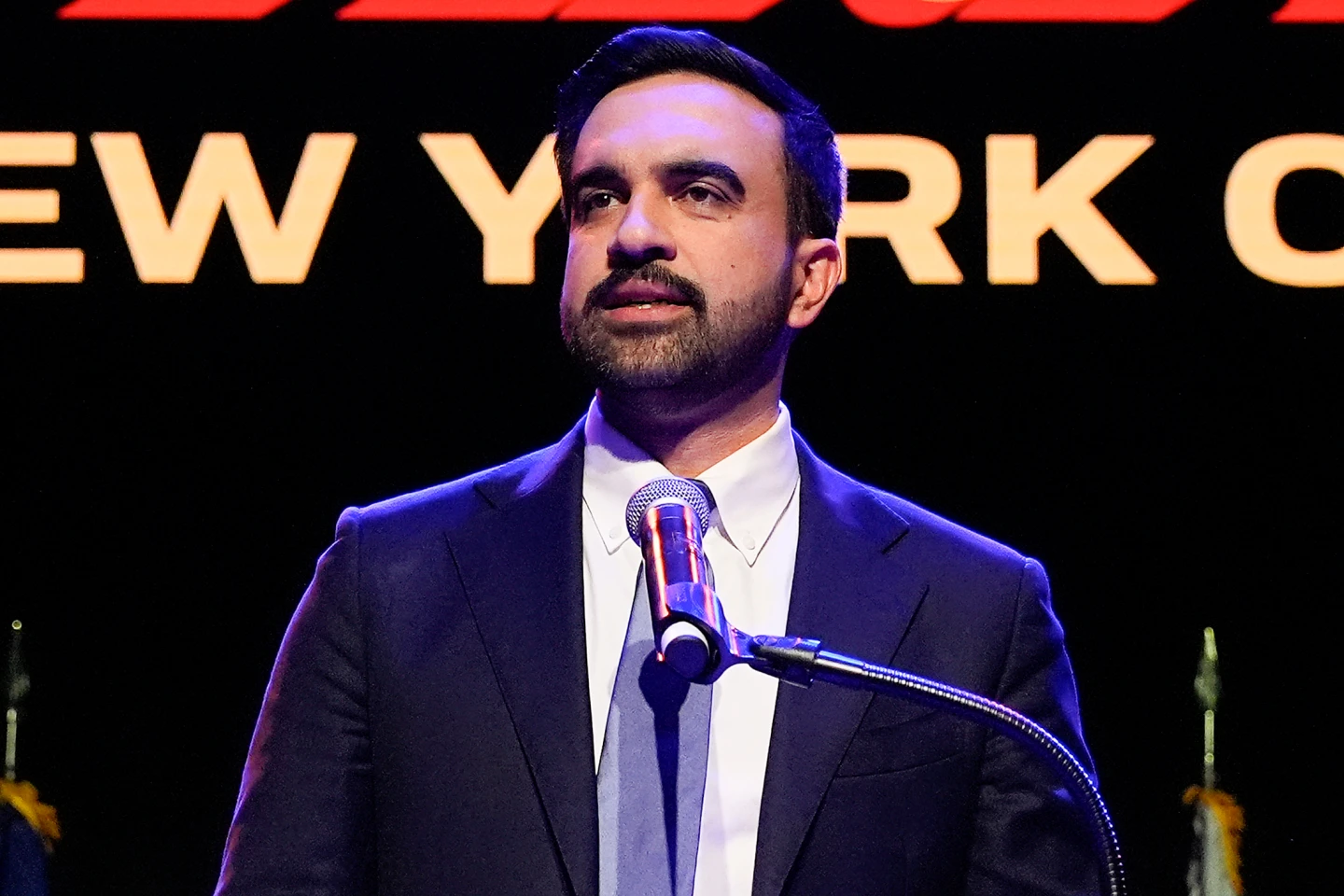

He will go into this election portraying himself as a safe pair of hands in an increasingly uncertain world. But Orban is trailing in most opinion polls, after his government was shaken by the meteoric rise of opposition Tisza party leader Peter Magyar.

Senior Hungarian officials have been hinting for months that they believe the war in Ukraine could be over by the end of the year - a seemingly absurd claim, until news of a planned summit in Budapest between Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin broke last month.

Orban hopes to persuade Trump to ease the pressure on Hungary at least until the election when the pair meet in Washington.

Despite warnings of price hikes, there is no data - so far at least - to suggest that consumers in Hungary would pay more for energy if they shifted away from Russian oil.

As the seagull flies, Omisalj is only 44 miles (70km) from Trieste. Seaborne oil from Kazakhstan, Libya, Azerbaijan, the US and Iraq could soon be flowing through the Adria pipeline to Hungary too.

Orban is about to find out how persuasive the US president can be.