This week's trial of three undercover operatives, accused of helping the Kremlin to wage a hybrid warfare campaign to destabilise France, sounds like a surefire recipe for drama, sophistication, and intrigue. If only.

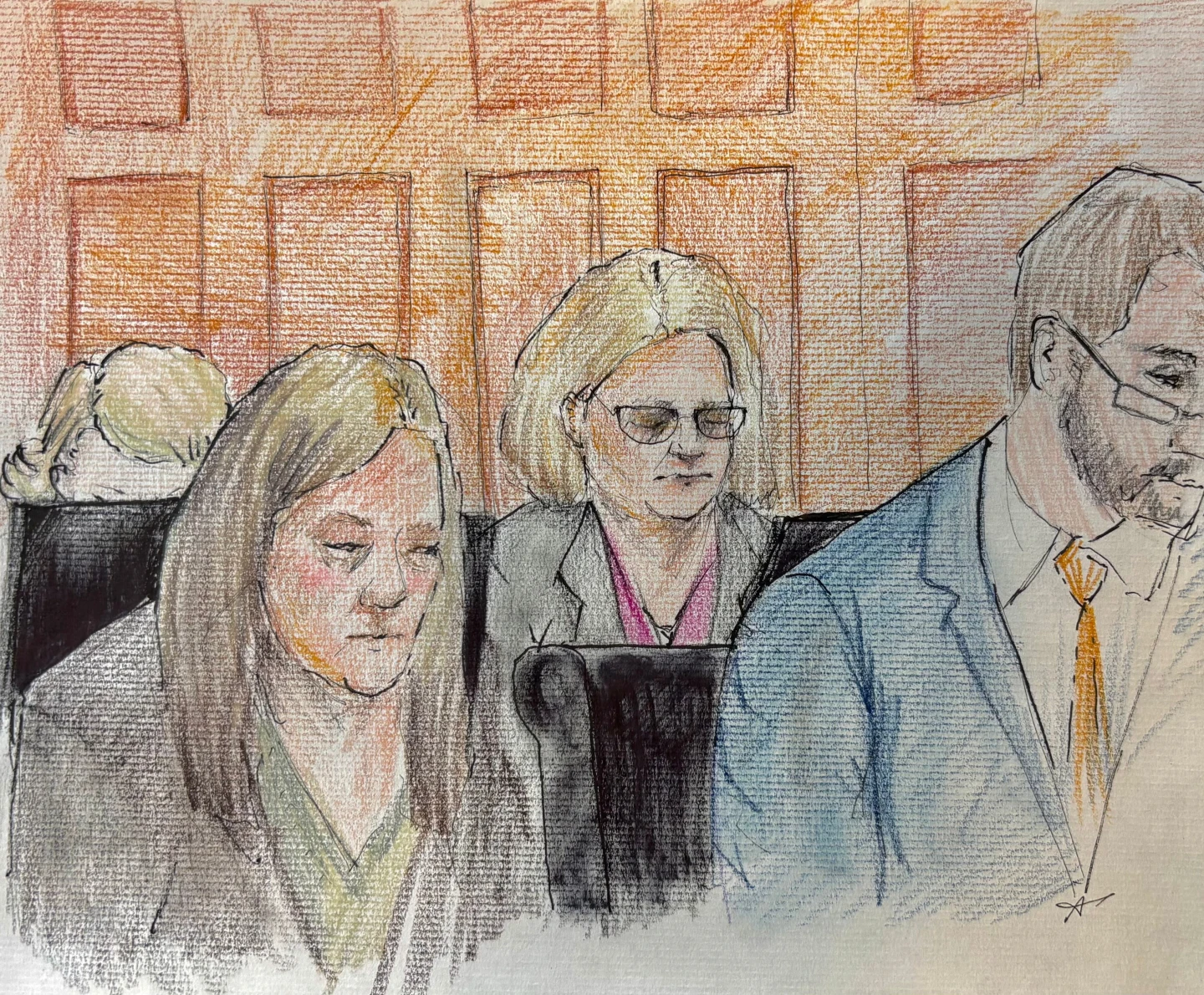

Over the course of three days, in a spacious, pine-panelled courtroom on the northern edge of Paris, the case against three seemingly unremarkable Bulgarian men, seated behind glass and shadowed by three police officers who seemed absorbed with their own mobile phones, unfolded with all the panache and excitement of a half-whispered lecture in a library.

I had absolutely no idea where we were.

I did it for the money.

In the future, I plan to get involved in charity work.

These few lines from the men's testimony may help convey the general tone. All three were jailed on Friday for two to four years.

But to bemoan the barely audible banality of it all – the dull motives, the mumbled attempts to shift blame, the sullen complaints about prison life and unsatisfactory psychiatric evaluations - is to miss the truth. The banality is the whole point.

Like the cheap drones that both Russia and Ukraine now use to patrol their front lines, the three men on trial at the Palais de Justice in Paris represent a low-budget evolution of modern hybrid warfare. Improvised and startlingly effective.

Rising in turn inside their glass cage, Georgi Filipov, Nikolay Ivanov, and Kiril Milushev admitted carrying out the acts but denied working for a foreign power as well as antisemitism. Early one morning in May 2024, on the banks of the River Seine in the heart of Paris, the three men conspired to spray red paint - and filmed themselves doing so - on the Wall of the Righteous, a monument to those who saved French Jews from the Holocaust during World War Two.

Thirty-five red handprints were left on the Shoah memorial, along with five hundred more elsewhere. This was the first in a series of symbolic attacks: pigs' heads placed outside mosques, coffins left ominously by the Eiffel Tower, and Stars of David painted in various locations around the capital.

Each event was swiftly broadcast around the world - not just by regular media outlets, but also by automated Russian social media trolls seeking to undermine European stability.

France, with its political and social divisions, presents a tempting target for the Kremlin. Traditionally, the Kremlin might have used deep cover agents for sabotage, but why rely on expensive formal assets when disaffected individuals can be recruited for low costs?

Filipov, for instance, claimed he was simply there to earn money for his child support obligations, allegedly receiving €1,000 plus expenses. In court, he attempted to deflect blame, noting past poor decisions related to tattoos and his appearance in inflammatory social media images.

All three men sought to blame a fourth, Mircho Angelov, who remains at large but is alleged to have Russian intelligence connections. The court's verdict reflects a complex web of motivations and highlights the dangerous new landscape of political subversion and its all-too-human participants.

Over the course of three days, in a spacious, pine-panelled courtroom on the northern edge of Paris, the case against three seemingly unremarkable Bulgarian men, seated behind glass and shadowed by three police officers who seemed absorbed with their own mobile phones, unfolded with all the panache and excitement of a half-whispered lecture in a library.

I had absolutely no idea where we were.

I did it for the money.

In the future, I plan to get involved in charity work.

These few lines from the men's testimony may help convey the general tone. All three were jailed on Friday for two to four years.

But to bemoan the barely audible banality of it all – the dull motives, the mumbled attempts to shift blame, the sullen complaints about prison life and unsatisfactory psychiatric evaluations - is to miss the truth. The banality is the whole point.

Like the cheap drones that both Russia and Ukraine now use to patrol their front lines, the three men on trial at the Palais de Justice in Paris represent a low-budget evolution of modern hybrid warfare. Improvised and startlingly effective.

Rising in turn inside their glass cage, Georgi Filipov, Nikolay Ivanov, and Kiril Milushev admitted carrying out the acts but denied working for a foreign power as well as antisemitism. Early one morning in May 2024, on the banks of the River Seine in the heart of Paris, the three men conspired to spray red paint - and filmed themselves doing so - on the Wall of the Righteous, a monument to those who saved French Jews from the Holocaust during World War Two.

Thirty-five red handprints were left on the Shoah memorial, along with five hundred more elsewhere. This was the first in a series of symbolic attacks: pigs' heads placed outside mosques, coffins left ominously by the Eiffel Tower, and Stars of David painted in various locations around the capital.

Each event was swiftly broadcast around the world - not just by regular media outlets, but also by automated Russian social media trolls seeking to undermine European stability.

France, with its political and social divisions, presents a tempting target for the Kremlin. Traditionally, the Kremlin might have used deep cover agents for sabotage, but why rely on expensive formal assets when disaffected individuals can be recruited for low costs?

Filipov, for instance, claimed he was simply there to earn money for his child support obligations, allegedly receiving €1,000 plus expenses. In court, he attempted to deflect blame, noting past poor decisions related to tattoos and his appearance in inflammatory social media images.

All three men sought to blame a fourth, Mircho Angelov, who remains at large but is alleged to have Russian intelligence connections. The court's verdict reflects a complex web of motivations and highlights the dangerous new landscape of political subversion and its all-too-human participants.