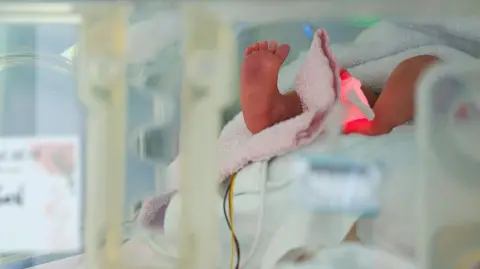

When Keira's daughter was born last November, she was given only two hours with her before the baby was taken into care.

“Right when she came out, I started counting the minutes,” Keira recalls. The moment her baby, Zammi, was taken from her arms felt like a part of her soul died. Now, Keira is one of many Greenlandic families on the Danish mainland fighting to get their children back.

Children were removed from these families following parental competency assessments known as FKUs, which Denmark has now banned for Greenlandic families following decades of criticism. These tests assess whether parents are fit to care for their children and often take months to complete.

Supporters of these assessments argue they provide an objective analysis of parenting capabilities, while opponents criticize them for being culturally biased and ineffective in predicting potential parenting skill.

Unfortunately, many Greenlandic parents are disproportionately affected by these measures, with studies showing they are 5.6 times more likely to have their children taken into care compared to Danish parents. In May, the Danish government promised to review hundreds of cases involving Greenlandic children but progress has been slow.

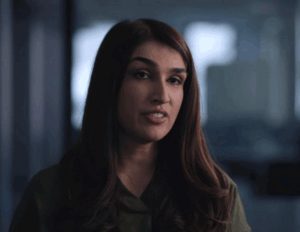

Keira, whose assessment deemed her unfit based on questions that felt irrelevant to her life, is determined to fight for her child.

“I will not stop fighting for my children. If I don't finish this fight, it will be my children's fight in the future,” she emphasizes, even as she prepares for Zammi's first birthday without her.

Stories like Keira's are part of a broader struggle faced by Greenlandic families, as they navigate cultural misunderstandings and fight against systemic biases in a quest for recognition and justice.