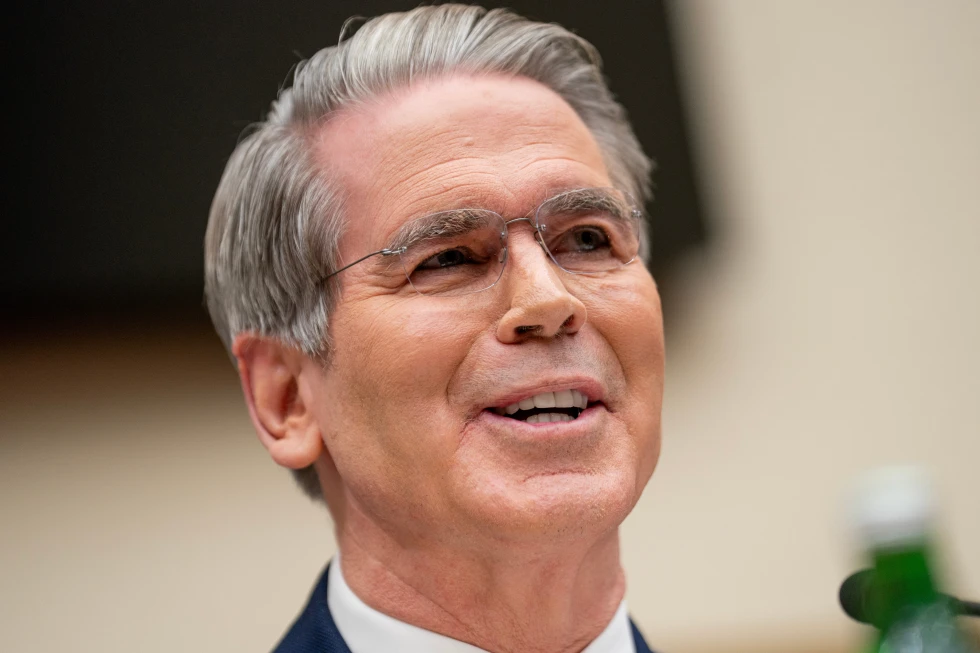

US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has been the point-person entrusted with selling financial markets on some of President Donald Trump's riskiest economic gambles: sweeping global tariffs, trade talks with China and preparations to install a new leader at the US central bank. But Bessent's trickiest task may just be the White House bet on Argentina.

The US stepped onto the scene in mid-September, responding to a plunge in the peso - the Argentine currency - which officials feared could imperil Trump ally President Javier Milei and his party in looming midterm elections. Bessent said the US would do whatever was needed to stabilise the situation, calling the country a key ally in the region.

In political terms, the US intervention - which included purchases of pesos and the establishment of a $20bn (£15bn) currency swap line that gives the Argentine central bank access to dollars - was a success for Milei. His party not only fended off losses in the midterm elections but made inroads, strengthening his position.

But whether the US intervention in the country will be a success financially is another question. The peso has fallen roughly 30% this year, including roughly 4% over the last month. The drop came despite the US commitments - and a modest rally after the election. It's an indication of the ongoing risk. At the end of the day, the US could find itself holding a pile of pesos worth much less than they were originally.

The intervention in Argentina was a highly unusual move - especially from a White House known for its 'America First' approach. Milei has endeared himself to conservatives in the US with his embrace of free-market reforms and radical spending cuts. He has met frequently with Trump, who has called him his 'favourite president'. But the US has rarely offered financial bailouts to other countries - especially in a case that posed no wider financial stability risks - and direct purchases of a struggling emerging market currency are unprecedented, says Brad Setser, senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Adding to the risk is Argentina's long history of currency devaluation and debt default, including most recently in 2020. Few are positioned to be as aware of the potential pitfalls as Bessent, who made his name as a currency trader working for George Soros. This time, Bessent finds himself on the opposite side of similar gamble. He has defended his moves, invoking the spectre of fellow South American country, Venezuela, and arguing that failure to shore up Argentina as a US ally could lead to destabilisation in the region.

Analysts have estimated the US has purchased as much as $2bn worth of pesos so far - hardly an earth-shattering figure. But Democrats have criticised the help at a time of White House spending cuts and an ongoing government shutdown, accusing Bessent of wanting to protect finance 'buddies' with investments in the country. Though the peso was buoyed by US support, most analysts believe it may still be overvalued.

As the economy progresses, Argentina faces continued challenges toward financial stability. The question remains: is the US ready to support Argentina for the long run, or will this be just a short-term fix?

The US stepped onto the scene in mid-September, responding to a plunge in the peso - the Argentine currency - which officials feared could imperil Trump ally President Javier Milei and his party in looming midterm elections. Bessent said the US would do whatever was needed to stabilise the situation, calling the country a key ally in the region.

In political terms, the US intervention - which included purchases of pesos and the establishment of a $20bn (£15bn) currency swap line that gives the Argentine central bank access to dollars - was a success for Milei. His party not only fended off losses in the midterm elections but made inroads, strengthening his position.

But whether the US intervention in the country will be a success financially is another question. The peso has fallen roughly 30% this year, including roughly 4% over the last month. The drop came despite the US commitments - and a modest rally after the election. It's an indication of the ongoing risk. At the end of the day, the US could find itself holding a pile of pesos worth much less than they were originally.

The intervention in Argentina was a highly unusual move - especially from a White House known for its 'America First' approach. Milei has endeared himself to conservatives in the US with his embrace of free-market reforms and radical spending cuts. He has met frequently with Trump, who has called him his 'favourite president'. But the US has rarely offered financial bailouts to other countries - especially in a case that posed no wider financial stability risks - and direct purchases of a struggling emerging market currency are unprecedented, says Brad Setser, senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Adding to the risk is Argentina's long history of currency devaluation and debt default, including most recently in 2020. Few are positioned to be as aware of the potential pitfalls as Bessent, who made his name as a currency trader working for George Soros. This time, Bessent finds himself on the opposite side of similar gamble. He has defended his moves, invoking the spectre of fellow South American country, Venezuela, and arguing that failure to shore up Argentina as a US ally could lead to destabilisation in the region.

Analysts have estimated the US has purchased as much as $2bn worth of pesos so far - hardly an earth-shattering figure. But Democrats have criticised the help at a time of White House spending cuts and an ongoing government shutdown, accusing Bessent of wanting to protect finance 'buddies' with investments in the country. Though the peso was buoyed by US support, most analysts believe it may still be overvalued.

As the economy progresses, Argentina faces continued challenges toward financial stability. The question remains: is the US ready to support Argentina for the long run, or will this be just a short-term fix?