Beijing is not always the most welcoming place in winter.

Frigid air blows in from the north, blast-freezing the city's lakes and rivers and only the hardiest souls would dare to plunge into the icy water. And yet, in the last two months, leaders from around the world have accepted invitations to the Chinese capital.

There's been a flurry of visits from France, South Korea, Ireland, Canada, and Finland. The German Chancellor is due next month. And now among the western leaders making a beeline for Beijing is Sir Keir Starmer, the first British prime minister to visit China in eight years. He seems to be guaranteed a warm welcome, especially after the UK recently approved plans for a Chinese mega-embassy in London.

Officials in China had already warned their counterparts that they would not announce the prime minister's visit until this issue was resolved.

But both sides are now ready to get around the table and for the UK, dozens of new deals are on the line to boost the country's economy.

If the two sides could move ahead with a reasonable trading relationship, that is already an achievement, says Dr. Yu Jie, a Senior Research Fellow on the China, Asia-Pacific Programme at the Chatham House think tank. One major question is to what extent China sees visits by the likes of Starmer as part of a bigger geopolitical shakedown? And how close does it really think it can become with the UK?

For China, this is part of a charm offensive in the hope that some will now look at Beijing as a stable, predictable partner - in contrast to the US. It seemed to work with Mark Carney, the Canadian prime minister, who visited earlier this month. He has blazed a trail for other world leaders by traveling to Beijing and announcing a new strategic partnership with China. Even before his speech in Davos, Carney told reporters in the Chinese capital that the global order was at a point of rupture.

This was a dramatic turnaround for a relationship between two nations that had been in the deep freeze for a decade, and it will be music to President Xi Jinping's ears. US President Donald Trump, however, has threatened to impose a 100% tariff on Canada if Carney made a trade deal with China. The message from Washington appears to be that if you do a deal with one superpower, you risk the wrath of another.

Starmer has already tried to sidestep this geopolitical landmine, and before he got on the plane, he made it clear he will not choose between the US and China. Some analysts believe that the Chinese will be clear-eyed about their ability to cause a rift in the so-called special relationship.

What was once dubbed a golden age for UK-Chinese relations has evolved into what Starmer has called an ice age. But with so many difficulties to navigate, a full rekindling of the old relationship is unlikely - it is more realistically the start of a slow diplomatic thaw.

In the warmth of a pub in the Hutongs, a traditional area in Beijing close to Tiananmen Square, the bright piercing sound of Celtic pipes burst from two speakers, as Bowei Wang pours a pint of brown ale. He is one of a million Chinese people who've studied in the UK in the last two decades, dating back to that so-called golden era between the two countries. The beer is everything for me, Wang tells me as he takes a sip. This was one of the first ales he made in his Overtone brewery in Glasgow.

Fifteen years ago, when I was studying in Scotland, I said, 'Wow, British beer is so good, I want to bring it back to China in the future'. And so, he has. The beer is now a cross-cultural ale, brewed in Yoker in Glasgow, shipped to China, and served from a bar in Beijing where scenes from the film Braveheart play on one large television while Elizabeth I is on another.

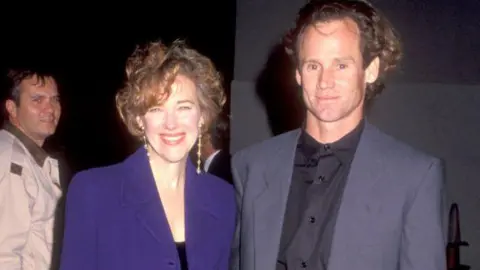

The defining photo from the golden era, when the UK advocated for closer economic ties, is a shot of the then Prime Minister David Cameron and President Xi sharing a pint and a basket of fish and chips at the Plough Pub in 2015. For the UK, this would be unthinkable now as it tries to navigate between its need to do business and its concerns over security. China remains a huge threat to national security as intelligence agencies continue to raise concerns about spying and intellectual property theft. There are also continuing threats to Chinese nationals who've fled the country and have tried to make the UK a haven and their home.

And from China's perspective, the 11 years since that meeting have seen it gain huge economic power. China is now responsible for around one third of all the world's goods, processes more than 90% of the world's rare earth minerals, and produces about 60 to 80% of all solar panels, wind turbines, and electric vehicles.

The relationship is changing; a potential new golden opportunity could be emerging, with both sides seeking to strengthen their economic ties amidst growing global tensions.