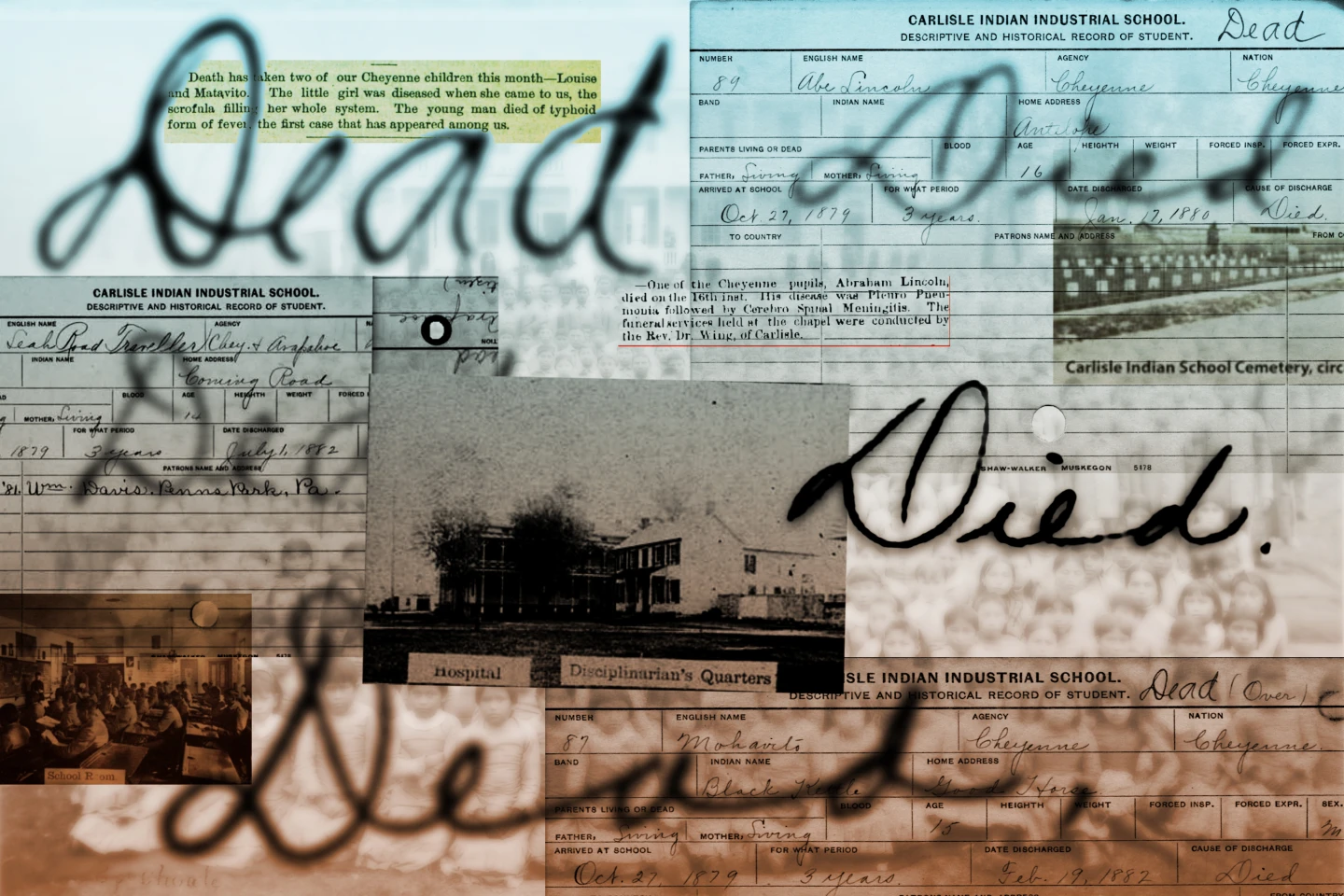

CARLISLE, Pa. — The journey of Native American children taken from their families to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School has come full circle with the recent repatriation of 17 of their remains to their home tribes. Among them were Matavito Horse, a Cheyenne boy, and Leah Road Traveler, an Arapaho girl, who arrived at the school in October 1879, unbeknownst to their fate.

Years later, as these children faced tragic ends—many succumbing to diseases like tuberculosis—fierce persistence from tribal communities led to their exhumation and return. In a powerful ceremony, the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes laid to rest their children at a cemetery in Concho, Oklahoma, fostering a long-awaited healing process for the affected families.

At Carlisle, children learned to work, losing their identities in the process. Some were baptized and trained in various trades, but their deaths were often attributed to neglect and harsh living conditions. Historian Preston McBride highlights how record-keeping was poor, often reducing a child's existence to a mere scrap of paper with conflicting details.

However, reported abuses were also rampant—physical and emotional harm at the hands of those responsible for their care. The recent findings and subsequent efforts to repatriate these children align with the U.S. government's acknowledgment of its failures at these institutions.

As the story continues to unfold, the partnership of tribes and advocacy groups is critical in securing the return of more children, with strong community support highlighted during memorial services acknowledging the sacrifices made and lives lost.

Efforts are underway to ensure that the continued exhumation processes are funded and executed with respect to the tribes, resonating with a shared understanding of justice and restoration.