Tanisha Singh is getting ready for work early one morning and cooking a simple curry for her lunchbox when she realizes she's out of tomatoes. Onions are already frying in the pan. Going out to buy vegetables is not an option, as local vegetable vendors won't be open. So Tanisha picks up her phone. On a quick-delivery app, tomatoes are available. Eight minutes later, the doorbell rings. The tomatoes have arrived.

What might feel remarkable in some parts of the world has become commonplace in Delhi and other big Indian cities. Groceries, books, soft drinks, and even the occasional iPhone can now be delivered to people's doorsteps in minutes. It's a convenience many don't strictly need, yet have quickly grown used to.

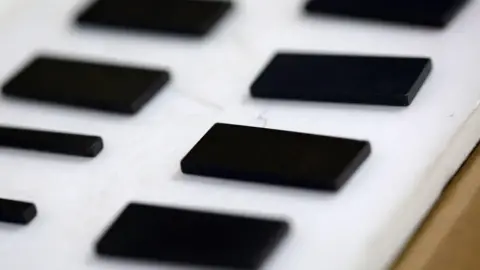

Unlike traditional retailers, platforms such as Blinkit, Swiggy, Instamart, and Zepto don't deliver from large supermarkets or distant warehouses. Instead, they operate out of small storage units embedded deep inside residential neighborhoods known as 'dark stores.' These facilities are typically located just a few kilometers from customers, allowing delivery riders to reach homes in minutes.

The process starts when an order pops up on the screen, prompting workers to pick, scan, and pack items into trademark brown paper bags almost robotically—a task done in under a minute, as store manager Sagar proudly states. The interplay between the packers and delivery riders is almost choreographed, ensuring efficiency and speed. Yet, the pressure on delivery workers like Muhammad Faiyaz Alam highlights the challenges of this rapid commercial evolution.

Alam, one of the countless gig workers in India, logs in each day to fulfill as many orders as possible. With earnings fluctuating based on volume and incentives, he faces a system designed for maximum output with little job security. Despite the pressures, consumers like Singh find themselves increasingly reliant on such conveniences, reflecting a profound shift in shopping habits that may lead to both comforts and challenges for the future.

What might feel remarkable in some parts of the world has become commonplace in Delhi and other big Indian cities. Groceries, books, soft drinks, and even the occasional iPhone can now be delivered to people's doorsteps in minutes. It's a convenience many don't strictly need, yet have quickly grown used to.

Unlike traditional retailers, platforms such as Blinkit, Swiggy, Instamart, and Zepto don't deliver from large supermarkets or distant warehouses. Instead, they operate out of small storage units embedded deep inside residential neighborhoods known as 'dark stores.' These facilities are typically located just a few kilometers from customers, allowing delivery riders to reach homes in minutes.

The process starts when an order pops up on the screen, prompting workers to pick, scan, and pack items into trademark brown paper bags almost robotically—a task done in under a minute, as store manager Sagar proudly states. The interplay between the packers and delivery riders is almost choreographed, ensuring efficiency and speed. Yet, the pressure on delivery workers like Muhammad Faiyaz Alam highlights the challenges of this rapid commercial evolution.

Alam, one of the countless gig workers in India, logs in each day to fulfill as many orders as possible. With earnings fluctuating based on volume and incentives, he faces a system designed for maximum output with little job security. Despite the pressures, consumers like Singh find themselves increasingly reliant on such conveniences, reflecting a profound shift in shopping habits that may lead to both comforts and challenges for the future.