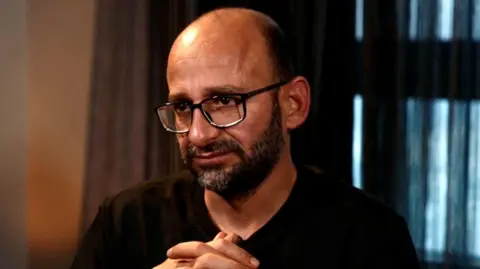

Earlier this month, a Palestinian diplomat called Husam Zomlot was invited to a discussion at the Chatham House think tank in London.

Belgium joined the UK, France, and others in promising to recognize a Palestinian state at the United Nations. Dr. Zomlot highlighted this as a significant moment, warning that this could be the last attempt to implement the two-state solution.

Weeks later, the UK, Canada, and Australia took that pivotal step. Sir Keir Starmer of the UK emphasized the necessity of a safe and secure Israel alongside a viable Palestinian state.

More than 150 countries had previously recognized a Palestinian state, but the addition of countries like the UK reflects shifting global attitudes toward Palestine. Palestine has never been more powerful worldwide than it is now, claimed Xavier Abu Eid, a former Palestinian official.

Yet, the fundamental questions about what constitutes Palestine remain. Palestine needs to meet four criteria for statehood, as outlined in the 1933 Montevideo Convention: a permanent population, a defined territory, a governing structure, and capacity to engage in international relations. Palestine can justifiably claim two of these but lacks a defined territory.

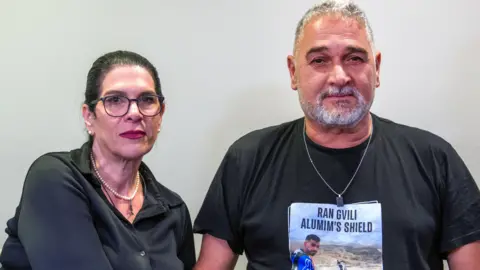

In the West Bank and Gaza, the populations are politically divided and led by rival factions—Hamas and the Palestinian Authority (PA). With no elections since 2006, political disillusionment is rife.

Even figures like Marwan Barghouti, a popular choice for leadership among Palestinians despite being imprisoned, highlight the lack of viable political candidates.

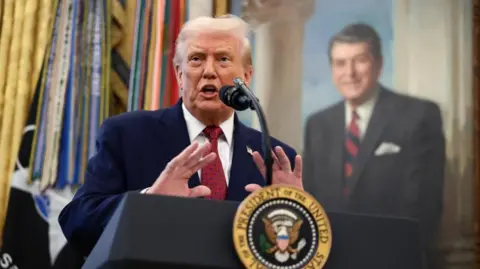

Benjamin Netanyahu's government remains opposed to Palestinian statehood, complicating the path forward. The emergence of actual governance remains uncertain, as does the overarching question of who would lead a Palestinian state, should it come to fruition.

As the region faces hardships, there's a consensus among voices like Diana Buttu that immediate attention needs to be directed toward stopping conflict before further political considerations.