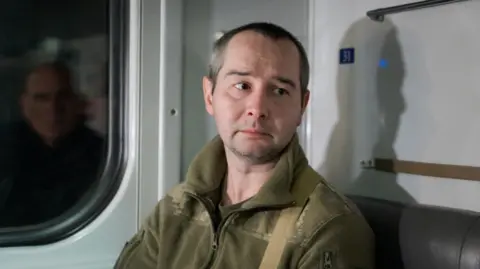

Since his release from a Russian prison, Dmytro Khyliuk has barely been off the phone. The Ukrainian journalist was detained by Russian forces in the first days of their full-scale invasion. Three and a half years later he's been released in a prisoner swap, one of eight civilians freed in a surprise move. While Russia and Ukraine have swapped military prisoners of war before, it is very rare for Russia to release Ukrainian civilians. Dmytro has been catching up frantically on all he's missed. But he's also phoning the families of every Ukrainian he met in captivity: he memorised all their names and each detail. He knows that for some, his call may be the first confirmation that their relative is alive.

There were celebrations last month when Dmytro was returned from Russia in a group of 146 Ukrainians. A crowd came out waving blue and yellow national flags, cheering as the buses carrying the freed men passed hooting their horns. Most on board were soldiers with sunken cheeks, emaciated after their years behind bars.

Stepping off the bus to a cheering crowd, Dmytro's first phone call was to tell his mother he was free. Both his parents are elderly and unwell and his greatest fear had been never seeing them again. 'The hardest was not knowing when you'll be allowed back. You could be freed the next day or stay a prisoner for 10 years. Nobody knows how long it's for.' Dmytro's account of his captivity is chilling, detailing beatings and relentless cruelty. He explains his first year was especially hard due to starvation, and he witnessed the even harsher treatment of soldiers.

Dmytro's family, living in their village outside Kyiv, faced constant distress during his absence, unsure of his fate. They shared a brief exchange with him, receiving a note he managed to send, assuring them of his well-being. While Dmytro has returned, many families still wait for news of their loved ones, with over 16,000 civilians missing in Ukraine. The challenges of negotiating their return remain complicated by the situation with Russia, making hope and connection all the more crucial in times of uncertainty.

There were celebrations last month when Dmytro was returned from Russia in a group of 146 Ukrainians. A crowd came out waving blue and yellow national flags, cheering as the buses carrying the freed men passed hooting their horns. Most on board were soldiers with sunken cheeks, emaciated after their years behind bars.

Stepping off the bus to a cheering crowd, Dmytro's first phone call was to tell his mother he was free. Both his parents are elderly and unwell and his greatest fear had been never seeing them again. 'The hardest was not knowing when you'll be allowed back. You could be freed the next day or stay a prisoner for 10 years. Nobody knows how long it's for.' Dmytro's account of his captivity is chilling, detailing beatings and relentless cruelty. He explains his first year was especially hard due to starvation, and he witnessed the even harsher treatment of soldiers.

Dmytro's family, living in their village outside Kyiv, faced constant distress during his absence, unsure of his fate. They shared a brief exchange with him, receiving a note he managed to send, assuring them of his well-being. While Dmytro has returned, many families still wait for news of their loved ones, with over 16,000 civilians missing in Ukraine. The challenges of negotiating their return remain complicated by the situation with Russia, making hope and connection all the more crucial in times of uncertainty.